Tool libraries are about repairing communities

The United States is in desperate need of expanded social infrastructure. The country’s growing network of tool-sharing libraries are just the thing we need to repair our communities.

When Josh Epstein decided to renovate his garage, converting it into a so-called “accessory dwelling unit” or ADU, he found himself in sudden need of a wide range of construction tools, but being a new homeowner he knew renovation could be costly.

Having moved into a new home with his wife and newborn just north of Seattle, Epstein found his way to the Northeast Seattle Tool Library (NESTL). Using the organization’s services, he was able to borrow tools that he needed at a fixed low cost - saving him thousands of dollars that would be needed to purchase the tools just to complete a single construction job.

We just needed a lot of heavier duty tools than we had. The main tool that was the most useful was a huge 20-foot scaffolding, which would be hundreds if not thousands of dollars. We also got a cement mixer and some serious roto-hammers. And I was just amazed by the place. It was so cool.

Being fond of the community and sharing associated with the tool library, Epstein began working with the organization and now runs the nonprofit that governs it.

I love the community of it. I love all the values of it, the sustainability on so many different levels: environmental, economic, and social.

Tool Libraries, or Libraries of Things (lending object rather than books), are a proof point of repair’s benefits to society. No matter who you are or where you live, something in your life is certain to break down from time to time. And, like the vast majority of people, you probably can’t pay to simply replace every item you rely on that stops working.

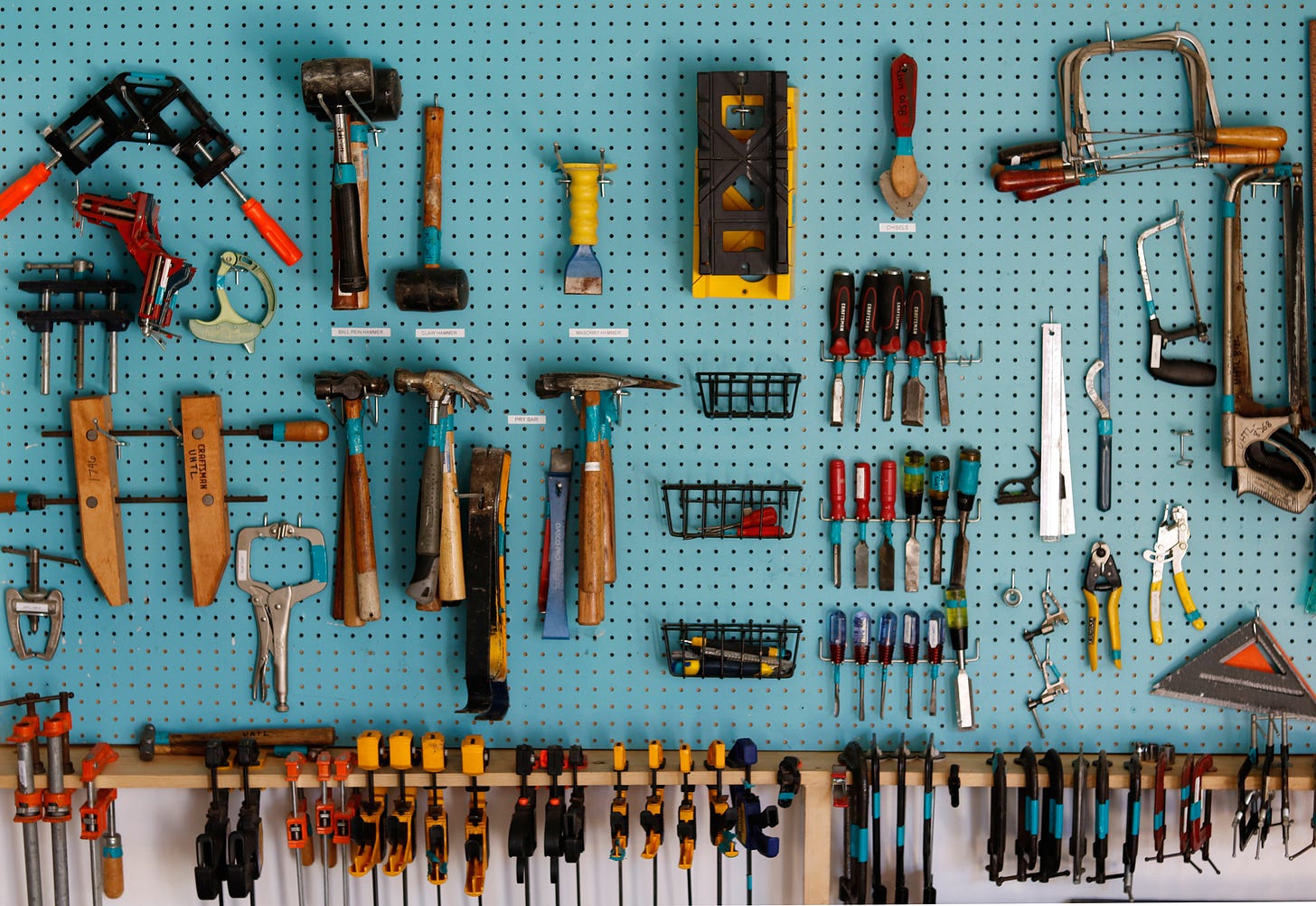

Repair, facilitated by tool libraries, are one answer. There are 60+ tool sharing organizations across the U.S. lending everything from hand tools to table saws. According to Local Tools there are ten tool sharing locations across the Seattle metro area, with the State of Washington offering grants to some for their waste-reduction activities.

After his experience finishing his garage, Epstein became a Program Manager at NESTL, where he helps coordinate more than 100 volunteers to maintain a community hub that allows its members to tap into a deep catalog of tools and other useful items. When I asked him if there was anything I ought to know about tool libraries he said:

“Tool libraries are a secret that shouldn't be a secret. They need more community and government support so that they are as commonplace as book libraries.”

Investing in our social infrastructure

That’s a good analogy. There are over 16,000 public libraries in the United States. Libraries are spaces that are open to everyone and free to access. Beyond books, they often provide Internet access, information for job seekers and public meeting spaces. Libraries serve as hosts for all manner of community programming.

Tool libraries have a similar mission. They offer a low- or no cost option to access tools, information, education, and support for fixing and repairing. These tools help facilitate repairs ranging from small fixes around users’ homes to full-blown renovations. It isn’t just for homeowners either: tool libraries can be used for landscaping, automotive repairs, and even electronics repairs.

Together with “book” libraries, tool libraries help form the “social infrastructure” of the communities they serve.

In his book, Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life, Eric Klinenberg discusses the importance of our social infrastructure, which he defines as “libraries, schools, playgrounds, parks, athletic fields, swimming pools” – basically any space that is open to everyone and usually publicly funded.1

If tool libraries have the potential to be a useful public service allowing people to repair things cheaply in addition to providing community programming and education, why aren’t we jumping to scale the tool library model?

The answer is that in the U.S. we are withdrawing, rather than expanding funding of our social infrastructure. Reports have documented the crises (plural) in funding for affordable housing, public health, and public education. Rather than growing, publicly funded institutions are struggling or failing in a country where nothing is off-limits to privatization.

Of course, the emphasis on privatization and profitability is part of a broader ideology of neoliberalism which has dominated the political sphere in the United States for decades.2

Neoliberalism has seeped into every corner of American life as markets take increasing priority over community. The consequences, according to social scientists, are increasing fragmentation and polarization of society. Data confirms that people are are no longer going to church, nor are they participating in social organizations at the rates they once did. The number of friends each American has is dwindling, anxiety is rising. Depression and suicide are increasing while trust in government and institutions declines.3

Tool libraries, repair clinics, and institutions like them run counter to the spirit of “profits-first and community second.” They bring people together to offer a service, connect disparate groups of people, educate their communities, and ultimately allow people to offer aid to one another.

This kind of thing practice has become all too rare, but it isn’t too late to reverse this trend.

Tool libraries: repairing communities

Klinenberg says that this trend of vibrant communities collapsing into atomized individuals that don’t connect with one another is a product of an infrastructure of isolation, not individual decisions.

Take this example: If you live in a community with no sidewalks, bike lanes, or public transit. You could bike to work but it is likely more dangerous and less convenient – so you choose to drive instead. In the same way, you might not have access to the tools or the know-how to fix your kitchen cabinet that broke, your only option is now to pay someone else to do it. A more robust social infrastructure would connect you with people and resources, giving you the tools and skills needed to accomplish your project.

Sure, you could go to a brand-name hardware store to talk to a salesperson representing a massive company who will give advice for the purpose of getting money from you. Or you could talk to your neighbor who lives down the street who you trust. It might seem like it isn’t a big difference between the two, but if a hurricane or flood damages your home – who would be there to help you?

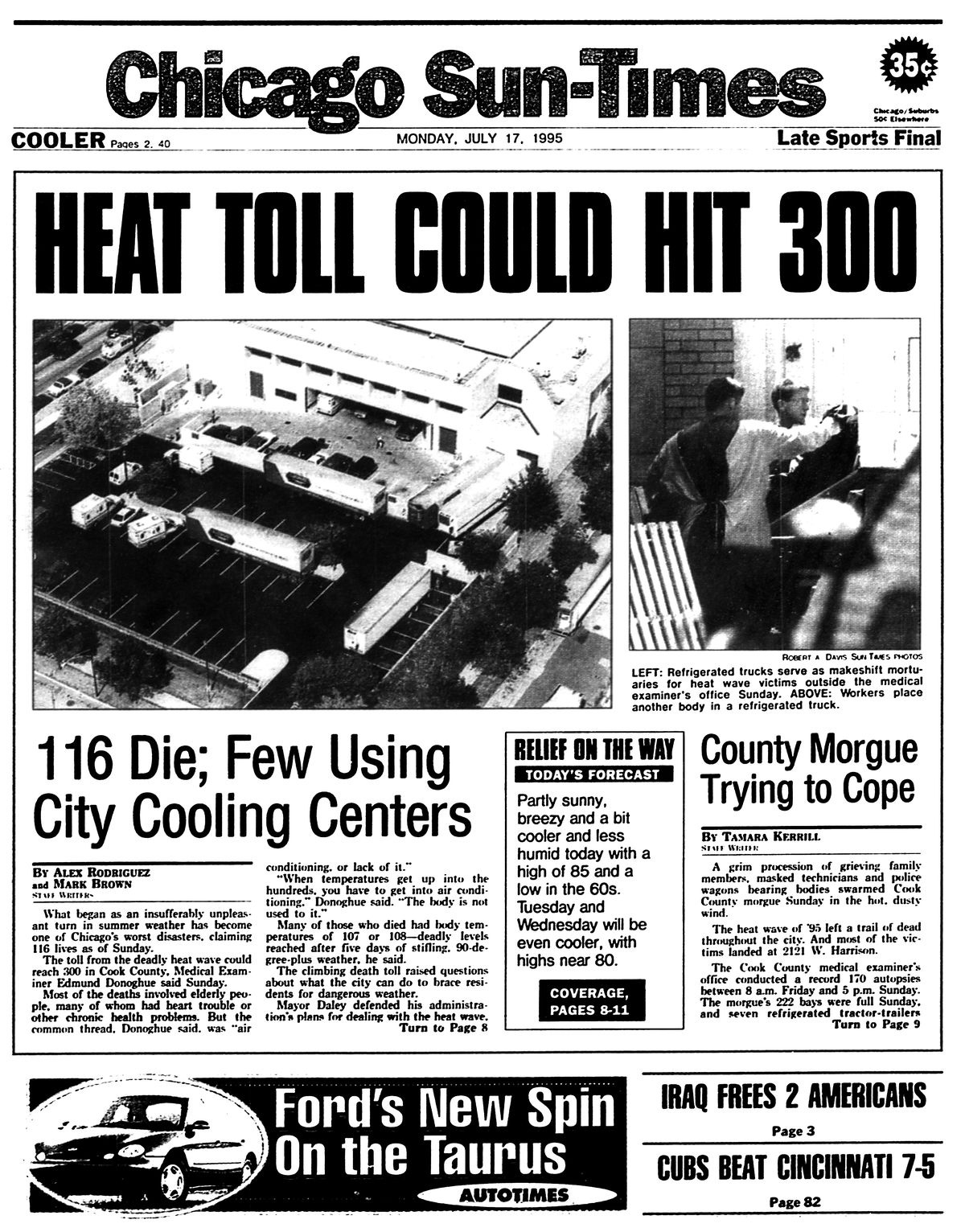

Klinenberg uses a similar example to explain the very real stakes at play for needing robust social infrastructure. During the Chicago heat wave of 1995, over five hundred people died, yet something surprising happened; his research found that social infrastructure was a strong predictor of death rates – meaning that working class neighborhoods that had strong social infrastructure saw fewer people die than the city’s richest neighborhoods.

“In 1995, residents of [the working class black neighborhood] Auburn Gresham walked to diners, parks, barbershops, and grocery stores. They participated in block clubs and church groups. They knew their neighbors – because they made special efforts to meet them, but because they lived in a place where casual interaction was a feature of everyday life. During the heatwave, these ordinary routines made it easy for people to check in on one another and knock on the doors of elderly, vulnerable neighbors.”

In the case of the Chicago heat wave, communities with more robust institutions, formal and informal, fared far better. The act of neighbors checking on one another through rolling blackouts and extreme heat kept more people alive than in more atomized and less connected neighborhoods. The same lessons can be drawn directly when exploring the benefits of tool sharing.

Funding social infrastructure requires resisting neoliberalism

Most two libraries I spoke with follow one of two models:

The first is a self funded model that relies on individual donations and other fundraisers, such as tool drives where tools that cannot be kept in storage and are sold for a profit. By serving large populations, they are typically able to keep membership fees low by using a system where people who earn more income pay more to ensure they are boxing out participants based on how much they earn.

The other model, which we should move to, is direct funding from governments. However, almost all tool libraries (even those with substantive government funding), are raising funds in some capacity outside government support.

Like many other community-level nonprofits, tool libraries running on the self funded model often need to give fundraising the same level of attention to fundraising as they do their daily operations. While there is no formal statistic tracking the failure rate of tool libraries, other tool libraries tell me that this constant need to fundraise makes the failure rate of launching tool sharing organizations high.

By forcing organizations like tool libraries fundraise constantly, we hinder their ability to serve the public while keeping a sword of insolvency hanging over their head. It also sends a signal that the services they offer are of lesser importance. The Pentagon isn’t holding bake sales to fund purchase and upkeep for its F-35s, why should tool libraries have to worry about keeping the lights on?

By funding tool libraries directly, we would confirm the the value they offer to our communities. It also lays the groundwork for communities to reap the social, economic, and ecological benefits of these programs: self-reliant, resilient and sustainable communities.

The appetite for tool libraries is growing, as they continue to prove the value they bring to their communities. And while the longstanding neoliberal values are difficult to unroot, there are heartening stories from every corner of the nation on how tool sharing and repair clinics are making housing more affordable, reducing waste, and bringing communities together.

There’s a great podcast interview with Klinenberg. Check it out!

Neoliberal policy has been the dominant mode of operation for both parties in the United States.