The Big Question: What Comes After Right-to-Repair?

Parts pairing, software controls and product design are the next frontier in the fight for a right to repair. Plus: US PIRG, iFixit call on FTC to create pro-repair rules for OEMs.

The evidence is piling up that the right-to-repair is both popular and politically viable. State-level laws, which have been the point of the spear in efforts to create a legal right to repair have been steadily making progress. In just the last year New York1, Minnesota, and California passed comprehensive electronics right to repair laws. Colorado legislators enacted right to repair laws granting access to repair information, parts and software for owners of power wheelchairs and agricultural equipment. In November, 2020, Massachusetts voters, by a vote of 3 to 1, expanded that state’s automobile right law to give vehicle owners access to telematics data needed for repair. And, last week, Maine voters outdid them: passing a similar state law with 84% of voters supporting the measure.

That victory also comes on the heels of Apple, a company that has been a core antagonist in the right to repair movement, supporting both California’s new repair law and calling for a federal repair law. The feeling of whiplash is strong when a company that has spent years digging its heels in on an issue beginning to cede ground when they know they are losing. The upcoming legislative season, which will start after the New Year is likely to see still more states bring forward right to repair laws in different flavors, with some percentage of those threading the needle of state legislators to be signed into law.

Of course, these recent legislative victories come after many years of work from advocates that have built power and common sense around issues of corporate power and over-consumption, and the shift could eclipse right to repair as we know it.

The question now: what comes next?

The next frontier of right to repair

There is a concept called the Overton window that helps us understand what is happening when companies like Apple back down on repair. Let’s consider a simple example:

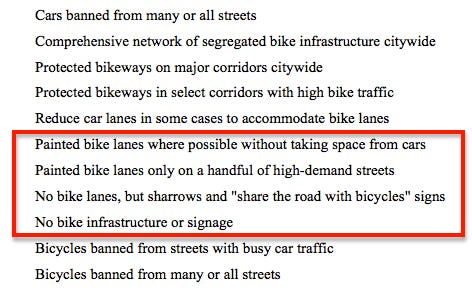

Let's imagine an imaginary city trying to decide on its bike regulations. When determining how to organize the city's transportation system, it needs to identify a set of policies that it could adopt. On the one hand, it could entirely prioritize bikers and ban cars altogether. Or it could be so pro-car it bans bicycles within its city limits. Most likely however, it will find a policy somewhere in the middle instead such as improving signage and implementing bike lanes. What the public (and the lawmakers they elect) consider to be reasonable policies that are worth discussing and debating, is called the Overton window (see in red below).

If - as seems likely - right to repair legislation continues to make headway through different geographic regions and industries, expect the Overton window to shift, and new baseline requirements for companies to move with it.

This shift was the focus of an article by Maddie Stone at The Verge, which notes that practices like parts pairing and manufacturer control over the supply (and cost) of replacement parts continue to make repairs impossible - or financially impractical.

“As long as repair is costly and complicated, it ‘will remain something only some people that are motivated by environmental reasons will choose,’” Stone quotes Ugo Vallauri, a co-director of the UK-based The Restart Project saying in her article.

Practices like parts pairing was also the focus of a New York Times article by Tripp Mickle, Ella Koeze and Brian Chen that ran on Sunday, “You Paid $1,000 for an iPhone, but Apple Still Controls It” (F**kin’ right!) That article cited research by iFixit that has documented the steady progression of restrictive parts pairing schemes, in which discrete and replaceable components are digitally tied to specific phone hardware, putting manufacturers in the position of being able to approve (or block) a wide range of repairs by owners or independent repair shops - driving up the cost and complexity of repairs.

As these high profile pieces suggest: the Overton window is shifting right to repair beyond just parts and information—moving instead toward concerns about software restrictions and design. The EU has moved to requirements like universal charging ports and eco-design requirements. As Ben Lovejoy at 9to5Mac notes: both design and part pairing could very well be the next domino to fall.

As these articles correctly observe: our thinking about the right to repair will need to shift and expand. As basic repair rights such as those enshrined by the laws in New York, Minnesota, California and Colorado take hold, other anti-repair tactics are now coming into focus, showing that the battle isn’t over once replacement parts, schematics and repair information are available. Software and design choices are already in the crosshairs of repair advocates, which means laws focused on the full lifecycle of goods (from production through disposal) are the logical next step to hold companies accountable.

Other News

PIRG, i-Fixit on Tuesday petitioned the FTC to adopt pro-repair rules for manufacturers. In their submission, PIRG and i-Fixit cited the growing practices of manufacturers to restrict consumers’ ability to repair their property and suggest a range of remedies, from rules that prohibit “unfair and deceptive trade practices limiting repair activities, to a repairability labeling system that would enable consumers to make informed purchasing decisions.” FTC rules would “provide a single nationwide standard, improve access and affordability for consumers of repair services, bolster independent repair,” PIRG and i-Fixit wrote.

The fight over car repair is about your data, two legal scholars have written. Writing for The Conversation, Leah Chan Grinvald, a professor of law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and Ofer Tur-Sinai, a professor of law at Ono Academic College write that concerns over cybersecurity and data privacy should not overshadow the need to preserve a competitive space in the auto repair sector and preserve the right to repair. “This matters not only for safeguarding consumers’ autonomy and ensuring competitive pricing, but also for minimizing environmental waste from prematurely discarded vehicles and parts.”

Apple Care produced $9 billion in profits annually according to a NYT report, citing part pairing as the prime tactic from Apple in juicing revenue for the company’s repair services.

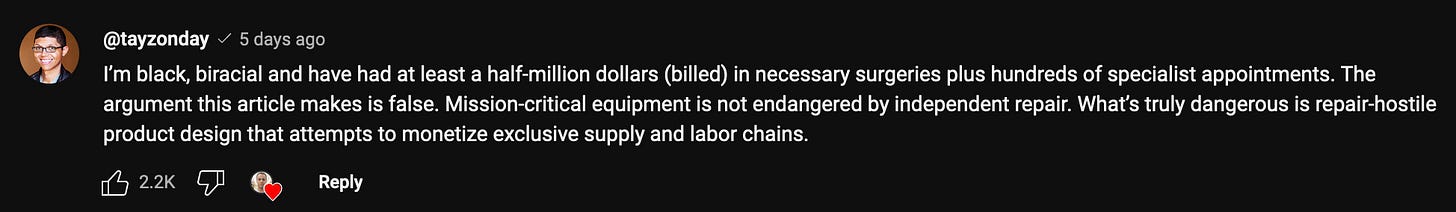

Louis Rossmann torches a lobbyist’s argument about Black people being hurt by medical device right to repair, saying this hollow pandering to equity is a bad faith argument and what others refer to as “Black Lives Marketing.”

Legal scholars say automotive right to repair is all about data, with software locks and other tactics keeping customers from accessing independent and self repair options. The only remedy to ensure access to data is included along with the purchase of a car is through legislation, with authors pointing to Massachusetts as a standard for other governments to follow.

Rep. Gluesenkamp Perez is beating the drum for automotive repair by promoting the REPAIR Act. She has noted that continuing to restrict repair will have serious (read: bad) implications for workers in the repair industry.

Games can’t upgrade existing Steam Decks by putting in screens from the latest model. Steam’s OLED screens from its newest model, the Steam Deck OLED, won’t be backwards compatible with older models, drawing questions about how upgraded devices can fuel obsolescence. You can find the teardown of the original Steam Deck here.

Worried about climate change? You don’t have to despair any longer, because Leonardo DiCaprio is bringing circular economy principles to the luxury watch industry!

A Right to Repair Act Could Reduce Millions of Tons of E-Waste A federal Right to Repair Act can reduce e-waste generation in the US, Vlad Turiceanu writes over at Earth.org. E-waste, with toxic components, is a growing problem due to difficulties in repair. Toxic elements like mercury and lead contaminate the environment. In the meantime, simply repairing devices could save US consumers $40 billion annually and support recycling, but coherent national policies are needed to overcome industry opposition.

While New York may have been first, it’s no shining example of right to repair legislation