Repairable Devices Shift Focus To Software Support

Could software be a barrier to longer-lasting devices? Plus, Massachusetts starts enforcing expanded auto repair law. And: electronics repair law moves forward in California.

Solutions to curbing our addiction to buying (and trashing) electronics often focus on physical components. Parts and information are a key piece for making sure we can repair the physical components that make devices work, but the role of software is often missed.

Media outlets (ourselves included) are quick to point out more flagrant examples of software fueling obsolescence. Whether its BMW’s heated seat subscriptions or Sonos’ almost bricking its smart speakers remotely, these point to extreme examples of the controls that corporations have over our devices long after we buy them.

But what about when software fuels obsolescence in less clear-cut ways?

Right to repair has limits, especially for software

Software is being stuffed into anything and everything. Your car, your thermostat, your toaster, and your lightbulbs can now be internet-connected, which is why U.S. households have 20.2 connected devices on average.

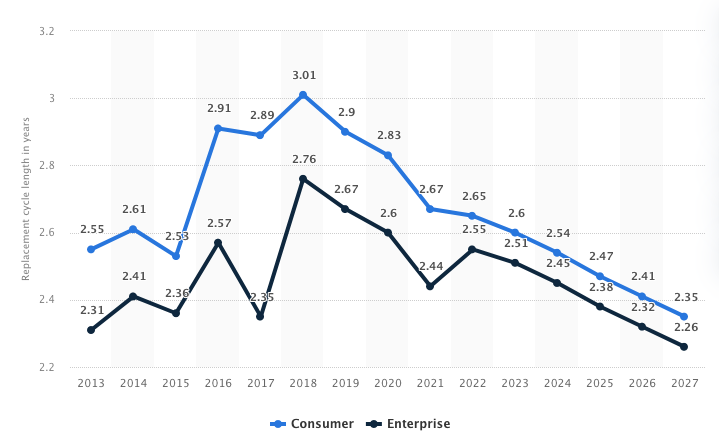

At the same time, products lifecycles are increasingly short as companies attempt to convince consumers to but the next shiny piece of tech. Statista shows phone lifespans hovering around 2.5~ years in the next five years.

Right to repair laws are expected to make these devices last longer as users get access to easier and cheaper repairs, but access to physical components and information on diagnosing problems doesn’t address the issue of needing updated software for these devices as their lifespans increase.

Let’s take our friends at Apple as an example: right to repair laws such as those passed in New York State and, more recently, Minnesota, will force the company to make parts and information available for phones and computers. However, it won’t stop Apple from prematurely revoking software support for older hardware devices. Fore example: the latest phone to officially have support revoked by Apple is the iPhone 6s which was released in 2015 - less than eight years ago. And there are rumors that the iPhone 7, 8, and X - all of much more recent vintage -can no longer run the latest iOS operating system updates. Practically, that means consumers with perfectly functioning iPhones will be forced to ditch those devices because they are no longer able to receive and run software updates.

The same dynamic is playing out in thousands of public school districts, where fleets of Chromebooks purchased to facilitate remote learning during the COVID pandemic are expected to have software support cut off by manufacturers within the next two to three years. As a report by US PIRG noted, that could lead to a tsunami of e-waste, while burdening cash strapped school districts with the need to replace perfectly functional hardware, with a tab totaling $1.8 billion.

Longevity vs. Security

In a perfect world, companies would offer consistent security updates for their Internet connected products. Regular software updates and patches can keep someone from stealing your financial information through your toaster or spying on you through your nanny-cam.

Paradoxically, as right to repair laws allow consumers and businesses to hold onto devices longer because they are able to fix them, the focus shifts from hardware to software, which needs to match the longevity of the hardware. But that costs companies money and, as it stands, manufacturers have few incentives to make that investment.

We wrote last week about the issues we face in a world where ownership is eroding as a software driven world moves deeper into a subscription-based economy. One manifestation of that is the growing trend of consumers being on the hook to “rent” things they already own. But subscription-based is one solution to maintaining support for older devices. And while savvier people are leaving Android and iOS to run their phones on open-source projects like GrapheneOS or Copperhead OS which will ensure they can receive updates, this won’t be the case for most people.

The EU has taken up this issue, proposing regulations that require OEMs to offer at least three years of OS upgrades and five years of security updates to the devices. However, if we envision our electronics running for 10 years, 20 years or more, it is almost certain that new rules will be necessary for manufacturers to provide software support, or enable others to do so for them.

Other News

Massachusetts’ attorney general began enforcing an expanded auto repair law on June 1st, after the federal judge overseeing the case denied a last minute appeal by automakers to block enforcement. Passed by voters with a nearly 3:1 margin in November, 2020, the law has been tied up in court ever since and still awaits a decision by federal judge Douglas Woodlock. Massachusetts new Attorney General, Andrea Joy Campbell, signaled in April that she would begin enforcing the law on June 1, absent a court ruling invalidating it.

The California state Senate passed Sen. Susan Eggman's “Right to Repair Act” (SB 244) on Tuesday with a 38-0, bipartisan vote, but still needs to pass the state assembly. The bill covers electronics and household appliances.

Medical device manufacturers are working hard to carve medical devices out of right to repair laws. By focusing on device complexity and cybersecurity, these groups argue that the highly regulated nature of medical device manufacturers, coupled with the lack of oversight on third-party service providers, should disqualify these devices from inclusion in right to repair legislation. Unmentioned: the ample evidence that constrained, monopolized medical device repair markets also pose a public health risk. Evidence of that cropped up during the pandemic, as hospitals struggled to bring ventilators out of storage to treat COVID patients, only to find authorized repair monopolies charging extortionate prices, or failing to scale to meet their needs.

Majority of DIY repairers struggle to access the parts they need, highlighting the need for improved access to spare parts and repair instructions for greater sustainability and to combat planned obsolescence. A new study found that 83% of DIY repairers struggle to identify and find replacement parts, while 30% face this challenge most of the time. Additionally, professionals also face difficulties in accurately identifying parts. The top request from both DIY repairers and professionals is for manufacturers to make it easier to accurately identify parts.

Quebec moves to ban planned obsolescence with Bill 29, proposed legislation aimed at encouraging the durability, reparability and maintenance of the products we buy.

Taiwan could implement repairability scores for products starting with smartphones and laptops, to minimize the environmental impacts of electronic devices.

Plastics are incompatible with a circular economy says Greenpace, which is calling for the capping and reduction of plastic production, ending virgin plastic production, and promoting refill and reuse practices. Greenpeace accuses the industry of deflecting blame and urges support for a plastics treaty that addresses the problems created by the industry.

Read the full report here.

Global Plastics Treaty negotiations have endorsed dangerous waste disposal practices, restricted NGO and community member attendance, and abandoned its commitment to addressing the full lifecycle of plastic pollution says nonprofit Just Zero. The zero-waste policy organization is criticizing the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) for allowing the fossil fuel industry to undermine the treaty and is urging the UN to reject industry influence.

It's undoubtedly the case that software is a threat to our right to repair - and though the EU does seem to be at least aware of the issue in a 'consumer rights' sense (i.e. mandating longer-term support, security updates etc), I do feel like we need a much broader movement to advocate for community control of software: if not by default (my strong personal preference!), then at least when a company decides it no longer wishes to support ageing hardware.

If a company wishes to abandon support for older devices, then I don't believe there are many compelling arguments as to why they should not, in tandem, be required to make the source code powering those devices / hardware publicly available. The 'intellectual property' argument cannot and should not override the freedom of people to use their devices as they wish, in my opinion!