Opinion: Killing Right to Repair Bills is Money Well Spent For Corporations

Corporations spend millions lobbying to defeat right to repair, adding billions to their bottom lines. But cracks are forming, as repair advocates start to win in statehouses across the U.S.

Follow the money

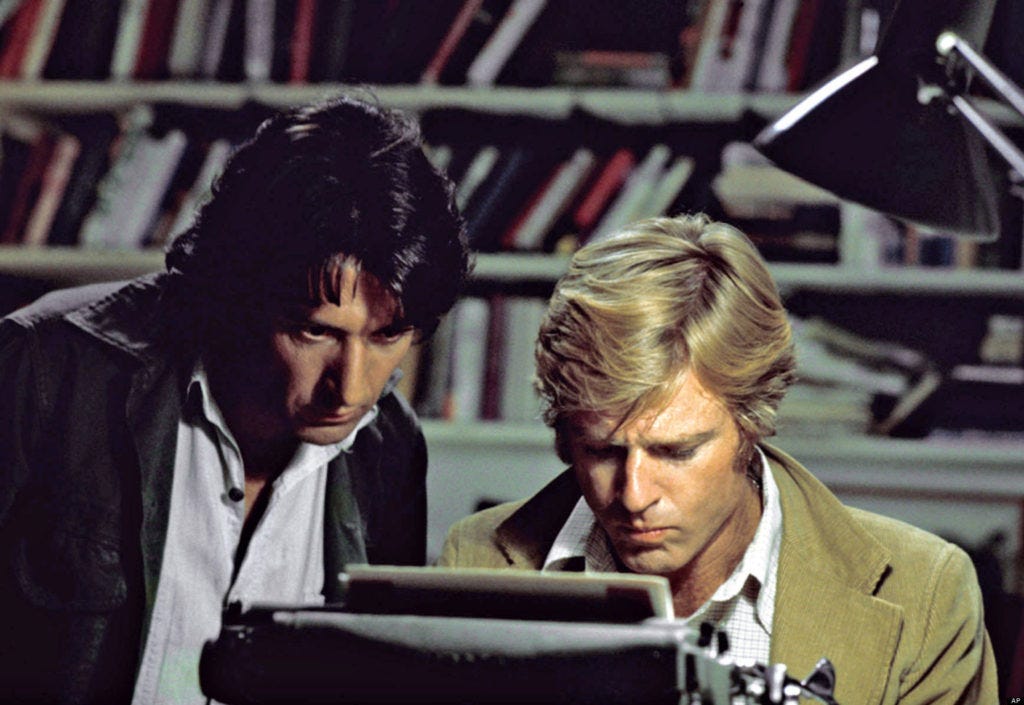

“Follow the money” was the famous (infamous?) advice of “Deep Throat,” the unnamed source that helped Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Karl Bernstein navigate - and expose - the convoluted Watergate scandal that brought down President Richard Nixon.

But “follow the money” is an adage that is equally useful in other inquiries, such as trying to figure out how 100 proposed state laws to create a legal right to repair have failed to pass state legislatures in the last 8 years, despite popular support for right to repair laws among the voting public that hovers around 70%.

Simply: campaign donations and intensive, paid lobbying are strategies that corporations have mastered to keep bills like those enshrining a consumer’s right to repair from cutting into their profits.

A report from the Technology Transparency Project (TPP) from earlier this year shows Apple doing just that. While Apple has tried to position itself as a leader in sustainability with initiatives like recycling and self-repair programs, it’s been caught giving money to groups that are actively fighting climate change legislation.

The TTP report highlights Apple’s “greenwashing” – a term describing the (cynical) effort by companies to cast environmentally costly business practices as “green” or “sustainable.” But the story also shines a light on the incredible reach and power that large corporations have in shaping state and federal laws in the U.S. It might also teach us a lesson about why a right to repair has been so difficult to achieve.

It all adds up: the math on anti-repair lobbying

Let’s better understand exactly why companies would be interested in interfering in the right to repair, starting with Apple:

Apple made $94.68 billion in net income over the course of 2021. Let’s say a federal repair law lets people keep their Apple iPhones for longer, delaying their purchase of the newest model. If such a development cuts into AAPL profits by even 1%, that is a loss of roughly $900 million for the Cupertino company.

And this isn’t a hypothetical. We have already seen examples of how increased access to repair options and decreases in the cost of repair directly impacts Apple’s bottom line.

In 2018, for example, Apple responded to “throttle gate” - a scandal in which the company was caught secretly throttling the performance of its iPhones - by easing its battery replacement policy: making battery replacements for its iPhones less expensive and easier to obtain. The result: Apple customers held on to their phones longer, replacing batteries affordably rather than upgrading to new equipment just to get the benefit of a new battery. The result for Apple? Sales of iPhones plunged 15% year over year, which decreased company revenue by $4 billion in the first quarter of 2018, from $84.3 billion from $88.3 billion from the same quarter a year before, according to a company press release. That was the first decline for both revenue and profit in a holiday quarter that Apple has posted since the iPhone’s introduction in 2007.

With $4 billion in losses on one side of the scale, it’s worth asking how much Apple needs to invest to prevent that measure from ever becoming law? Peanuts, by comparison. Apple spent just one half of one percent of that amount - $22 million - on lobbying and campaign contributions during the 2020 election cycle. And that figure encompasses all of the company’s lobbying activity - from climate to manufacturing - not just lobbying to hobble right to repair laws.

In other words, Apple and other companies like it can spend a microscopic fraction of the bottom line cost of progressive legislation to simply kill progressive legislation, and reap the benefits of inaction.

The bottom line is that campaign contributions and lobbying are so popular with corporations because they work. By lining the pockets of politicians, companies spend millions of dollars in order to save billions of dollars. From the business investment standpoint, that’s just smart.

TechNet: A prime offender

Apple is hardly alone. In the fight to repair, TechNet is a perfect example of how money infects politics. TechNet is a trade association that “champion[s] policies that foster a climate of innovation and competition, allowing America’s tech industry to flourish.” According to the Technology Transparency Project’s funding database, they are funded by every major technology company.

TechNet, works to directly influence policy on behalf of these corporations.

Our state team engaged on 661 bills in all 50 states and achieved a 90 percent success rate.

That is as clear an indication of political influence as there is. When it comes to right to repair, the most used argument they use (aside from the beloved exploding battery argument) is that it will open Pandora's box – giving criminals and hackers the keys to the castle to harm consumers as they please. They say as much on their website:

“TechNet will oppose any legislative proposals that would require original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to provision independent repair firms in the same manner in which they provision authorized repair providers within their networks because of the potential for troubling, unintended consequences, including serious cybersecurity risks, privacy risks, safety risks, piracy hazards, and barriers to innovation. Consumers, small and large businesses, public schools, hospitals, banks, and manufacturers all need reasonable assurance that those they trust to repair their connected products will do so safely, securely, and correctly.”

This argument about cybersecurity concerns has been used extensively. It’s also untrue. Organizations like TechNet are speaking directly with policymakers across the country to socialize these ideas about repair being unsafe, not to mention they represent the companies funding candidates in both parties.

And TechNet isn’t alone. Automobile manufacturers spent $25 million in 2020 lobbying against a single ballot measure in Massachusetts, Question 1, which requires automakers to make telematics data needed for service and repair available to independent repair shops and owners. That money paid for a campaign that played up the cybersecurity risks of the proposed measure. In the end, however, voters backed Question 1 by a huge margin - 74% to 26%. They have spent millions more on a federal lawsuit that has delayed implementation of the law by more than 2 years.

Ten trillion dollars (fighting right to repair)!

In spite of these corporate powers flexing their influence, the repair movement has seen legislative wins, like Colorado’s power wheelchair repair law. We’ve also seen the nation’s first electronics right to repair bill passed in New York state (though not yet signed into law).

Despite those successes, just this year we’ve seen bills die in Washington, California, and Nebraska to name a few. Each time, repair advocates point to lobbying as a chief cause.

And lobbyists’ tentacles reach far and wide even in states that have notched successes. A recent piece by the Times Union showed that lobbying efforts by organizations, TechNet included, had successfully narrowed the scope down the original New York Digital Fair Repair Act, carving out exemptions for certain sectors like medical devices and agricultural equipment.

A 2021 study by U.S. PIRG found that the companies that contribute to lobbying efforts against Right to Repair are cumulatively worth about $10.7 trillion. They include Tesla, Johnson & Johnson, AT&T, Lilly Inc., T-Mobile, Medtronic, Caterpillar, John Deere, General Electric, Philips, eBay, plus the “big five” - Google, Amazon, Meta, Apple and Microsoft. To reach this estimate, they totaled up the estimated market cap for each company, or the estimated total value of all their traded shares.

And the carve outs in the New York law were merely the cost of a (big) “win” for the right to repair: the first electronics right to repair bill to ever clear a state legislature. Prior to that, anti- right to repair lobbying had killed 100 separate pieces of legislation filed in 40 states since 2014 - a 99% success rate, according to data from U.S. PIRG.

It’s important to understand exactly how these state-level lobbyists accomplish what they want. If you’re a lawmaker the chances are you have a handful of issues that you are familiar with and an “expert” on. It’s not unusual for lawmakers to be on a number of committee assignments which means that the “niche” issue of right to repair can often allude to lawmakers themselves. So in these circumstances where you’re a lawmaker with little understanding of a particular issue, you could easily be inclined to listen to lobbyist talking points.

Gay Gordon-Byrne, executive Director at the Repair association, is no stranger to the anti-repair lobby. She’s often going head to head against industry lobbyists and has seen the same talking points recycled again and again.

“Because these are hired lobbyists, and they’re in the building all the time, they could be hired by ten different companies… Let’s say the American Heart association hires a lobbyist to get funding for the health community. That same lobbyist who is advocating for heart health is also advocating [against right to repair].”

Nathan Proctor, another seasoned right-to-repair veteran of U.S. PIRG explains another way:

“[Companies] hire these local lobbying firms and what do they do? They have [lobbyists] that are really well-known by lawmakers in the state. Why are they well known? Because they’ve been fixtures in state politics their whole career. And they donate money to the candidates and they hold fundraising parties for the [political] leadership… They’re like coworkers.”

Gordon-Byrne puts it simply: “for their own sanity, the [lawmakers] are chopping the bills up”. When a lobbyist (or ten) that lawmakers see as a friend/coworker or a threat to their reelection comes knocking on their door repeating talking points about the doomsday scenarios associated with letting people repair their own tractors or cars, they are very much inclined to believe them, Gordon-Byrne said.

Remaining optimistic (and persistent)

All that said, the right to repair movement has cards it can play. Chief among them: popular support among voters. A Morning Consult Poll from March found that nearly 7 in 10 voters polled back a legal right to repair.

And while it is often difficult to pin down exactly how decisions on legislation are reached, if repair advocates can get a better picture of how lawmakers are influenced by lobbyists, and take advantage of openings in state houses, we can use those same tactics to advance our agenda.

The Colorado wheelchair right to repair bill, which was signed into law by Governor Jared Polis, rose from the ashes of a failed effort to pass a more general right to repair bill in 2021. After emotional testimony by Colorado residents who relied on wheelchairs and were being subjected to extreme wait times for service and repair, legislators pushed a wheelchair-only repair bill in the 2022 session, which passed.

In other words, while power weighs heavily in the hands of corporations, they’re not bulletproof. And victories against such powerful interests are all the more impressive in the face of millions of dollars in lobbying arrayed to stop them. While the fight to repair might remains an uphill battle, we know money can’t buy everything.

We, the authors of

Repair: When and How to Improve Broken Objects, Ourselves

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-98908-8

are moderately optimistic:

"The Revolution Has Begun

The right to repair has received increasing attention in recent years. Technologies are changing rapidly, as are manufacturers’ attitudes to the right to repair. Every consumer has the right to buy something and, if it breaks down, to have it restored to its original condition by a repairer....}