Colorado Lawmakers Sing A Familiar Tune in Opposing Right to Repair: Google’s

When Colorado lawmakers met to debate a right to repair bill last month, they had lots of concerns - many provided courtesy of Google.

These are the best of times and the worst of times for the right to repair movement. In the United States, right to repair legislation has been proposed in more than half the states, including bills enshrining a right to repair agricultural equipment, medical devices as well as digital electronics like smart phones and laptop computers.

But those bills have faced a hostile reception. The electronics, home appliance, medical device and telecommunications industries have spent millions hiring lobbyists and working behind the scenes to defeat this legislation, with pretty good results. At last count, legislation in 15 states had been defeated or otherwise put on ice.

One of those states is Colorado, where House Bill 21-1199 is officially on hold and unofficially dead. This, after moving testimony before the House Business Affairs & Labor committee on March 25th.

Wheelchair Bound And Stranded? Next!

As reported by Vice, that event included heartbreaking testimony from disabled Coloradans who spoke about the dire situation faced by wheelchair bound residents in the state where one firm controls the lion’s share of “authorized” wheelchair repair and where manufacturer restrictions prevent owner and independent repair of power wheelchairs. For residents there, waits of weeks or months for simple repairs like battery and parts replacement are common.

Kenny Maestas, who relies on an electric wheelchair, talked about the difficulty he had getting a battery replaced including a 35 day wait for a visit from an authorized repair technician, rendering the wheelchair useless and Mr. Maestas immobile in the meantime, with an open wound that was exacerbated by his lack of movement.

Maestas said that the electric wheelchair company had the battery and spare parts in stock, but its policy required a technician to first “inspect the chair” before making a repair.

“You would think they would just bring the (battery or parts) required on their first visit and get the the wheelchair working immediately,” Maestas said. But that didn’t happen. It ultimately took another 28 days after the initial visit by a service technician before he was mobile again: more than 60 days in all.

“Rural Coloradans with disabilities deserve the right to repair routine fixes on their durable medical equipment,” he said. “It’s never appropriate to make a human being with a critical care need wait over two months for a repair that could have been completed in two days,” he said.

Michael Neal, a power wheelchair user since age 10, echoed those statements. “When problems do arise it often takes multiple trips and multiple weeks for each repair…A lot of it is the result of the (service) companies,” he said.

The committee members didn’t have a single question for either speaker. Not even a word of sympathy for their struggles.

While the prospect of disabled constituents stranded and immobilized for months, needlessly, didn’t arouse the passions of lawmakers, other issues did. For example: the implications of Colorado’s law for interstate commerce??!

Ownership Is What The Seller Says It Is!!(?)

How did the concerns of ordinary Coloradans end up on the back burner while arcane questions of interstate commerce sat front and center?

Credit the lobbyists for large technology firms, who have spread out in statehouses across the country this season to derail bills just like HB 21-1199 using whatever means and arguments they can. In the case of HB 21-1199, representatives from the likes of TechNet, the Consumer Technology Association (CTA) and AHAM (the Association of Home Appliance Makers) the Advanced Medical Technology Association (AdvaMed) and others lobbied hard against the law.

These groups have been successful in bending legislators to their viewpoint. In fact, as the Vice article pointed out, legislators articulated eye-popping and stilted pro-manufacturer and pro-Big Tech arguments in opposition to the bill.

Asked by one of the bill’s sponsors, Representative Steven Woodrow, whether she owned her iPhone or whether Apple owned it, Representative Shannon Bird responded that “ownership means what the seller means it to be and what your contract says.”

“When you sell something you can sell whatever bundle of rights you want to sell.” That was something “basic” about “ownership,” she explained (incorrectly) before likening a physical phone to Apple’s Internet music service Apple Music. (Spoiler alert: the definition of “ownership” in U.S. law is not “whatever the seller decides it to be.”)

Lobbyist’s Words, Lawmaker’s Lips

In other exchanges, the arguments made by legislators were more than just in line with Big Tech’s point of view. They were straight out off of Big Tech’s list of talking points. Case in point, Committee Chairman Dylan Roberts (D-26) put a question to the bill’s two sponsors that you can listen to here:

Cross border warranty issues? Interstate commerce? It’s a really curious question for a hearing on a state consumer protection law. In fact, it was one that I’d never heard posed before in a Right to Repair hearing, by either side. (And I’ve attended a lot of them.) There’s a good reason for that: the Federal Magnusson Moss Warranty Act already makes it pretty clear that so-called “carry back” provisions that require you to return warrantied products to the point of service are illegal.

So where did that question come from? We don’t know exactly. What we do know is that the question about honoring warranties for products that cross state lines was included in an email sent to the bill’s sponsors shortly before the hearing by Mary Kay Hogan of the Fulcrum Group, a communications and political consulting firm based in Denver that was hired by Google.

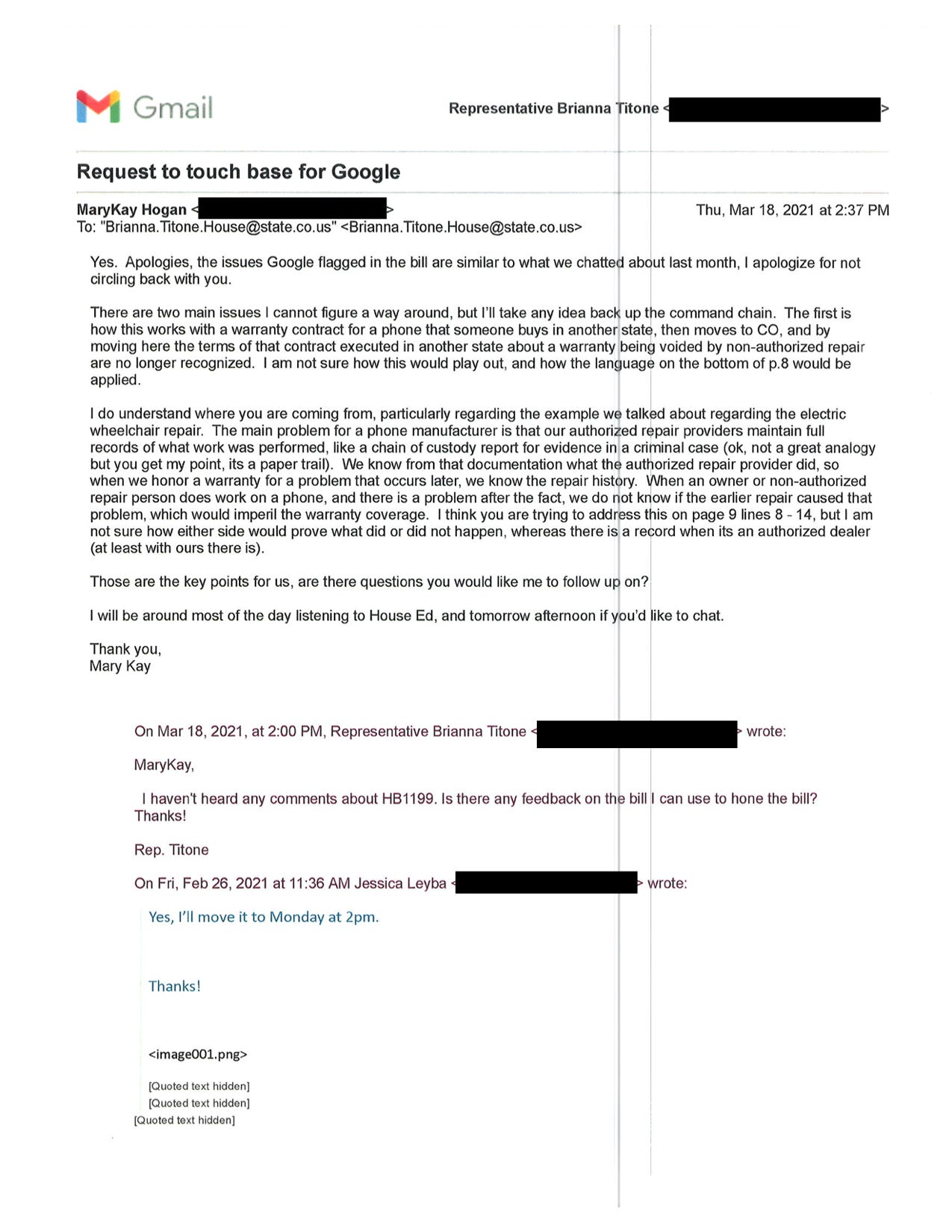

According to a copies of emails obtained via an open records act request by Fight to Repair, Hogan began reaching out to Colorado legislators including the bill’s sponsor Representative Brianna Titone in early 2021 about the right to repair.

“I am reaching out to see if we could touch base sometime in the not to (sp) distant future on behalf of my Google client,” Hogan wrote to Titone in an email dated February 18. “I only started representing them in January and it is my understanding that last year someone may have gotten off on the wrong foot with you on the right to repair bill or another issue? At any rate, I’d like to remedy whatever happened and be able to communicate with you effectively for them.”

The two appear to have had at least one Zoom meeting in late February. Then, in an email dated March 18, just a week before the hearing, Hogan wrote to Titone in response to a request for any feedback on the HB 21-1199 bill. There were “two main issues I cannot figure a way around,” she wrote. “The first is how this works with a warranty contract for a phone that someone buys in another state, then moves to (Colorado), and by moving here in terms of that contract executive in another state about a warranty being voided by non-authorized repair are no longer recognized.”

Hogan was writing in regard to language in the draft legislation that made clear the law would not “alter the terms of any contract or other arrangement in force between an original equipment manufacturer and an authorized repair provider, including the performance or provision of warranty or recall repair work.”

The supposed conflict is really a non-issue, as the Magnusson Moss Warranty Act of 1975 already forbids tying of warranties to authorized repair providers or parts. You’re entitled to have a device under warranty serviced by whomever you want. It’s a common misunderstanding among the general population, and one that manufacturers do their best to not educate the public about. But it’s also a question that can be answered with, literally, one Google search. So much for not being able to “figure out a way around” it.

As for how Ms. Hogan’s question ended up on Chair Roberts’s lips? While we don’t have a similar copy of an email sent to Chair Roberts, we do know that he and Ms. Hogan were scheduled to meet via Zoom on March 12 based on a copy of an email invitation to that meeting obtained from the Representative.

It is unclear whether the meeting with Hogan put the question about interstate commerce and warranties on Roberts’ radar, or whether the opposite is true: that Roberts fed the issue to Hogan who then repeated it in an email to Titone a week later.

What is clear is that there are deep similarities in the Hogan email and the question Roberts posed to the bill’s sponsors. Let’s take a look:

“There are two main issues I cannot figure a way around…The first is how this works with a warranty contract for a phone that someone buys in another state, then moves to (Colorado), and by moving here the terms of that contract executed in another state about a warranty being voided by non-authorized repair are no longer recognized. I am not sure how this would play out.” - Mary Kay Hogan, Fulcrum Group, email to Rep. Titone March 18, 2021

“I have a question about the warranty aspect of this. If someone buys a product in either Colorado or out of state and they come to Colorado and they are able to do this repair, does that violate the warranty and if it doesn’t how is that warranty protected with regard to interstate commerce?” - Rep. Dylan Roberts, hearing on HB 21-1199 March 25, 2021

I reached out to Rep. Roberts via e-mail and phone and haven’t heard back on this coincidence, but promise to update this post when I do. But, to be fair, Rep. Roberts wasn’t the only committee member to allude to questions about the impact of the law on interstate commerce.

Colorado Rep. Kyle Mullica worried aloud about the prospect of Colorado “forcing another state to follow the laws we pass here,” and about what might happen if a Colorado resident exercised the state’s new right to repair law for a phone that wasn’t purchased in state. “What about an inverse situation where someone purchases an iPhone in Florida and then moves to Colorado?”

The Really Depressing Part…

The really depressing part of all this isn’t so much that lobbyists have the ear of lawmakers. (Duh!) Rather, its how large the interests, priorities and words of large corporations and their phalanxes of lobbyists, PR flacks and media consultants loom in the minds of the men and women who are ostensibly elected by the people to serve in the best interests of the people. As Vice ably noted in their article, lawmakers seemed utterly incurious about the plight of disabled Coloradans who were literally immobilized by a lack of adequate repair choices for motorized wheelchairs. Repair proponent after repair proponent testified and, when the Chair asked if there were any questions, there were none. Where lawmakers did engage, it was around noodling issues of legal precedent, intellectual property law or copyright - exactly the kinds of things that corporations, not voters, care about.

Equally depressing, answers to the “questions” they did have about warranty, copyright, or the bill they were being asked to consider were all readily available and most were just a Google search away. Curious reps might have taken a minute to familiarize themselves with the Magnusson Moss Warranty Act and, thereby, found the answers to many of their questions. Or they could have refreshed their memories about how interstate commerce works. Legal eagles like Rep. Bird might have reviewed concepts like “tortious interference,” the common law concept that prevents one party in a contract from causing economic harm to another, before stating blithely that sellers get to impose any terms they want on buyers.

A Message to Legislators: RTFB!

You might ask: ‘why don’t the legislators just do their jobs’? Read the bill. Get answers to the questions it raises - or have their staff do so. Come prepared to ask questions of expert witnesses, not just wave them away with a “thank you for testifying!”

Jeremy Soller, a principal engineer at System 76, a Denver-based maker of computers, summed it up best. When asked in the hearing what he would say to those who raised objections about cyber security or copyright infringement or physical safety, Mr. Soller said simply “I don’t believe that they have read the bill. If they did, they would understand the information you have to provide your customers is not information to bypass security measures, to produce a dangerous device, to bypass EPA regulations or hack the device or bypass copyright restrictions. These are not things the (right to repair) bill allows for. The bill allows customers to do a repair that may be blocked by the manufacturer without the bill.” Indeed.

In other words, RTFB, legislators (Read the f**king Bill.) RTFB.